LF Examiner continues its retrospective of 24 years of publishing with this article about one of the most unusual giant-screen films ever made: Pandorama by Nina Paley. As she describes below, the camera-less three-minute film was literally made by hand, every frame drawn directly on blank or reused film stock.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2000 issue of MaxImage! (as LF Examiner was originally known).

by Nina Paley

For most of my adult life, I’ve plied my trade as a newspaper cartoonist. After seven years of self-syndicating a weekly comic strip called “Nina’s Adventures,” I signed on with Universal Press Syndicate to write and draw a daily strip, “Fluff.” Cartooning had been my lifelong passion, but the rigorous schedule of producing a daily feature turned it into a monotonous job. I grew artistically impoverished and desperate to explore a new medium. So at the start of 1998, purely as recreation, I returned to a long-abandoned interest of my youth: Super-8 filmmaking.

One thing led to another, very quickly. I shot Luv Is…, my first clay-animated film, on Super-8. Two months later, I’d bought a cheap Russian 16mm wind-up camera, and shot my second clay short, I ♥ my Cat. I drew my next film, Cancer, directly on 35mm film, á la Norman McLaren. I had a contact print made, and in late 1998 Josephine Scherer, projectionist at the Fine Arts Cinema in Berkeley, offered her empty afternoon theater as a screening room.

When I arrived at the Fine Arts projection booth, Josephine was entertaining some guy who had worked in the same theater decades earlier, and just wanted a look around for old time’s sake. Would I mind if he and his friend stuck around while Josephine projected Cancer? No problem.

The guy turned out to be Chris Reyna, president of the Large Format Cinema Association, and his friend was Judith Rubin, editor of the LFCA newsletter. They gave me their cards, said something about an “animation and experimental task force,” and mentioned an upcoming screening in Los Angeles. The idea had been planted: by that night, I became obsessed with making a cameraless 15/70 film.

I recklessly bought a last-minute ticket to LA. In addition to the groundbreaking premiere of More, I saw the 15/70 blow-up of the Absolut Panushka shorts. I had previously seen them in 35mm, and the contrast in LF was striking. Serendipitously, I happened to be seated right next to Don MacBain, whose short, Fire,was an excellent example of composition, timing, and sound design with the giant screen in mind. While many of the Panushka shorts were brilliant on smaller screens, they were incomprehensible in an IMAX theater. Conversely, I suspected Fire wouldn’t work so well on video, but on that huge screen, it was magic. I saw a variety of other shorts, all of which were right on the cutting edge of LF and all of which had much to teach me.

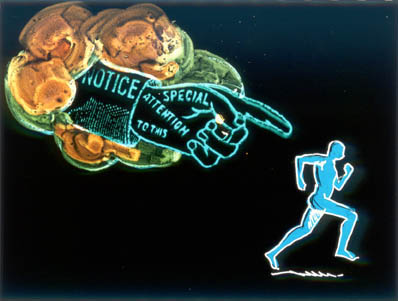

Shortly thereafter, I came up with a rough project proposal for Pandorama. I chose the theme of Pandora’s Box because it was a familiar story, and offered a structure that could support all kinds of images and techniques. The size of the film made new worlds of cameraless techniques possible, and I wanted to try them all.

Proposal in hand, I began schmoozing as I had never schmoozed before. Don MacBain put me in touch with editor Dave Bartholomew, who was incredibly supportive and donated two big fat rolls of clear 70mm leader, along with invaluable advice. Judith Rubin helped me track down filmmakers who might have 70mm junk footage to spare. Kelly Moren at Imagica USA gave me a crash course in internegatives, interpositives, and 65mm intermediate vs. 70mm print stock. Unfortunately, the LFCA Animation Task Force was still recovering from More, so I wasn’t able to get LFCA sponsorship. But so many people in the industry were so helpful and supportive, I was able to produce Pandorama myself.

I had already made plans to spend the summer of 1999 with relatives in Switzerland, so I dragged two suitcases of junk footage and leader along with me. I set up shop in a dusty utility room in my cousins’ back yard. My studio consisted of a used office desk, a 70mm tape splicer, a pair of rewinds, and a few 16mm split reels, which held the 70mm cores with clamps (except when they slipped and the whole contraption fell apart). When the house had visitors, they slept in that room. A neighborhood cat forced its way through the window screen and slept on my work occasionally. I kept the place as clean as I could, but I knew the folks back in LA would have had seizures if they’d seen my working conditions. I didn’t worry about it; I figured dust, fingerprints, and cat hair would add “texture.” It was an experimental film, after all.

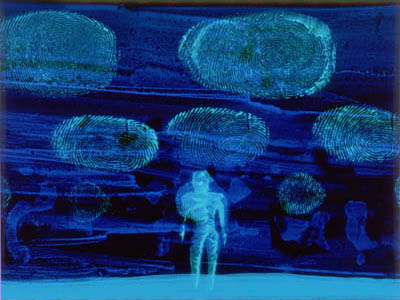

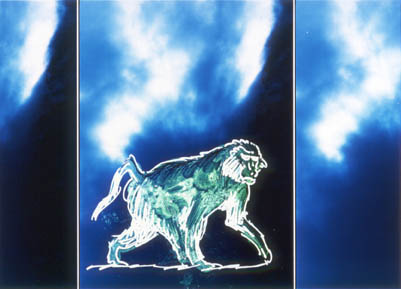

I spent about three months actually making the approximately 2,500 images. After a week of drawing thousands of framelines, the real fun began. Much to my delight, the emulsion on the 70mm leader accepted all kinds of media, including water-based ink. I applied rubber stamps (carved out of bike tire inner tubes) directly on the emulsion, and made “clouds” out of my fingerprints. I put some 8/70mm junk footage on its side, drew new framelines every 15 perfs, and used it as a background for animation traced from old Muybridge photographs. The effect was a background that moved something like a tracking shot, which the Muybridge images, taken with multiple still cameras, also resembled.

I built a tiny wooden rig with brads as registration pins and a mini fluorescent flashlight as a backlight. I’d pass 35mm or 5/70mm junk footage through the rig vertically and 15/70 film horizontally. Frame by frame, I’d trace little bits of the 35mm picture I wanted, generating a primitive kind of rotoscopy.

I used the same rig as a mini-“animation desk,” drawing original animation in pencil on tiny pieces of paper, then inking them on strips of clear leader instead of cels. I drew on both sides of the Estar film; with Rapidograph film ink on the smooth side and colored ink on the emulsion side. Sometimes I would scratch away at the emulsion-side drawings, creating both black and white line work on a colored field, reminiscent of Conte crayon on gray paper. I found a free 3-D animation program on the web, used it to design wireframe “flyover” scenes, printed each frame out at approximately 15/70 frame size, and inked them one at a time directly on clear leader with colored markers. Finally, in a kind of twisted tribute to the latest developments in digital film output, I taped three strips of leader side by side and ran them through my desktop inkjet printer at 360dpi.

I had no way of testing or viewing any of the animation while I worked on it. That had to wait until I was back in the US, where I had a video transfer made from my original element. I was much relieved to see that most of my experiments had been successful. I studied and ruminated on the video until I had a mental picture of how I wanted to edit together the 40 or so scenes, and in one 45-minute session with Avid editor Mike Tuomey, we slapped together a (very) rough cut.

Since I had essentially no budget, getting a print made was an adventure in itself. To make a very, very, long story short, I secured generous donations of 65mm and 70mm film from Kodak, and printing and processing services from CFI, without both of which Pandorama would never have seen the light of a projector lamp. I had my original 70mm hand-drawn element contact printed; although an optically printed negative might have looked nice, I wanted Pandorama to be completely cameraless. I had an IP made from the IN, and tape-spliced together segments from each, so that the final print would include both positive and negative images.

Meanwhile, I was working on sound. A friend of mine collects strange and obscure music, and I found the perfect piece on one of his mix tapes. It was “Yeah Yeah,” by Scottish glam-punk band The Revillos, recorded circa 1979. Tracking down the vinyl was a long and difficult task, and contacting the band was even harder, but eventually I had both my soundtrack and the band’s blessing.

My friend’s tape also contained an excerpt from a 1950s Christian Sunday School record, which was so ironically appropriate I just had to use it. So I created a 26-second visual introduction to go with the sound. This consisted of 48 frames of black leader, followed by two frames of art, followed by more black leader, two more frames of art, etc. I created this segment simply to have something to look at while playing the sound excerpt, but I was delighted with the results. In a giant-screen theater, the bright frames every two seconds blast the eyes like photon torpedoes, and the intervening black provides a dark background on which to contemplate the retinal after-image, until the next light blast. Once again, necessity proved the mother of invention, and the process of experimental filmmaking yielded results superior to what I could have imagined.

Through a blur of frenzied phone calls and frequent flights to L.A., a 70mm print of Pandorama got made in time for a private industry screening at the Sony IMAX Theater at Metreon in San Francisco on December 6, 1999 (see Shorts, MaxImage! November 1999). Finally I got to see it on the giant screen for which it was intended. I can’t adequately describe the experience; I’d thrown an entire year of my life into those three minutes of film, and for the first time, I felt it had been worth it.

Last month Pandorama had its second screening, at the LFCA conference in LA. Imagica recently made a 35mm printdown, which is on its way to international short film and animation festivals. But Pandorama was made for the giant screen, and I hope that someday it will play as a short for the LF theatergoing public.

Nina Paley is an animator, illustrator, cartoonist, and filmmaker whose films since Pandorama include Sita Sings the Blues (2008) and Seder Masochism (2018). Her website is ninapaley.com.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.